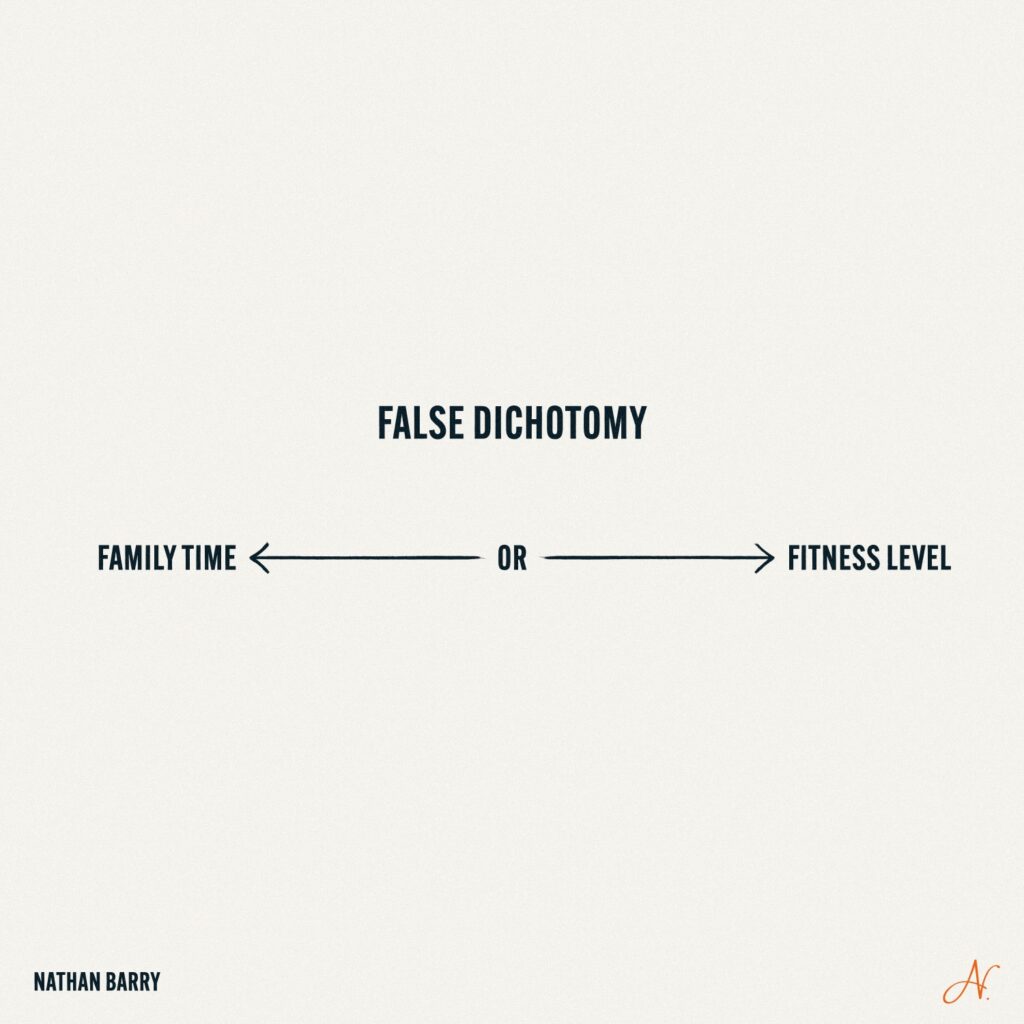

A friend recently told me he couldn’t start working out because it would take time away from his kids. “I only have so many hours,” he said. “It’s either family time or fitness.”

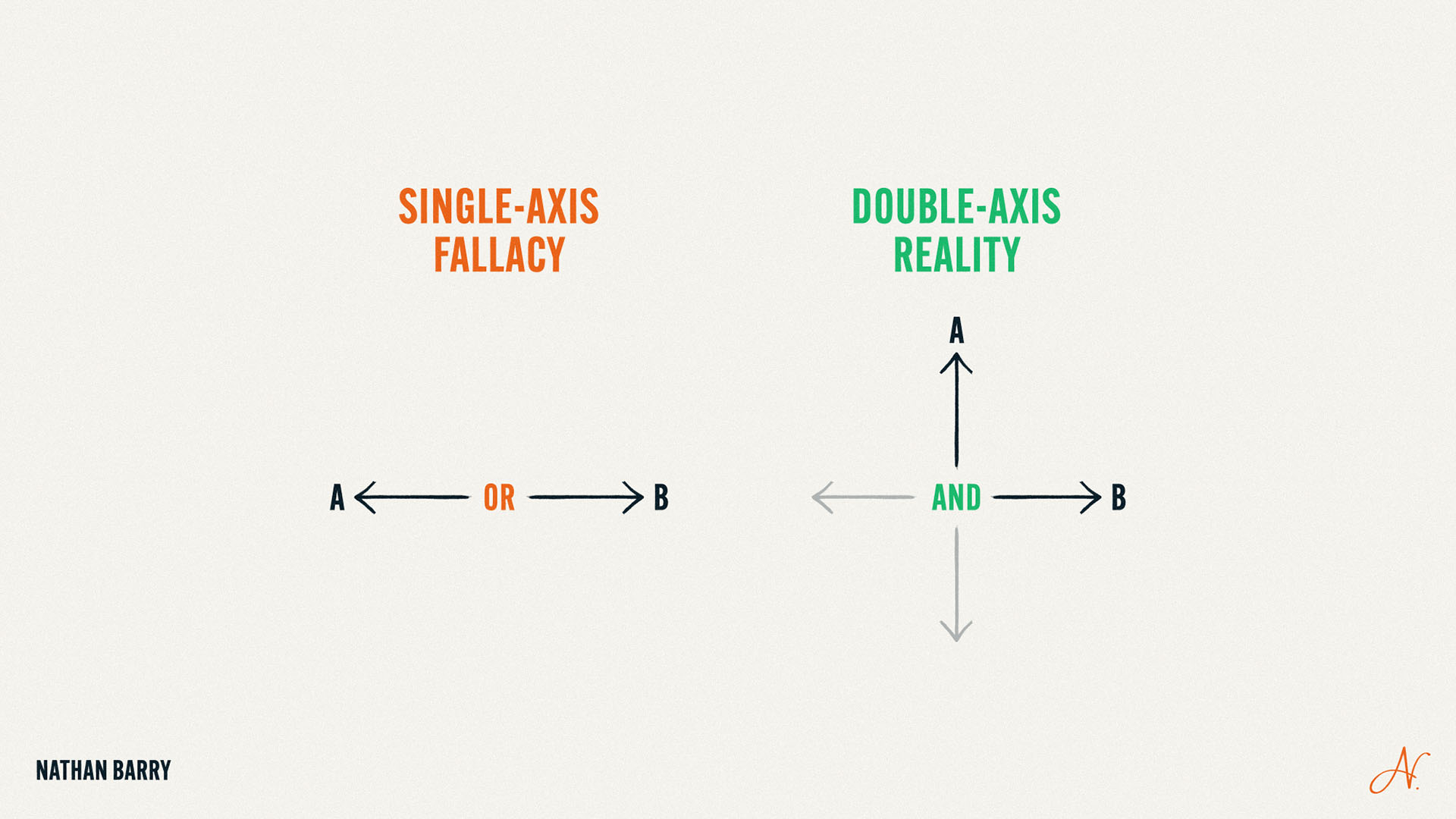

You probably know about false dichotomies, where someone forces you to choose between only two options when more exist. But there’s a subtler trap I call the Single-Axis Fallacy, and it’s limiting your potential in ways you might not realize.

What is the Single-Axis Fallacy?

The assumption here is simple: Do you want to spend time with your family or do you want to be really fit? More time exercising means less time with family.

This puts both things at odds with each other on a single axis. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find tons of exceptions. There are individuals who hit all their fitness goals AND are very present with their families.

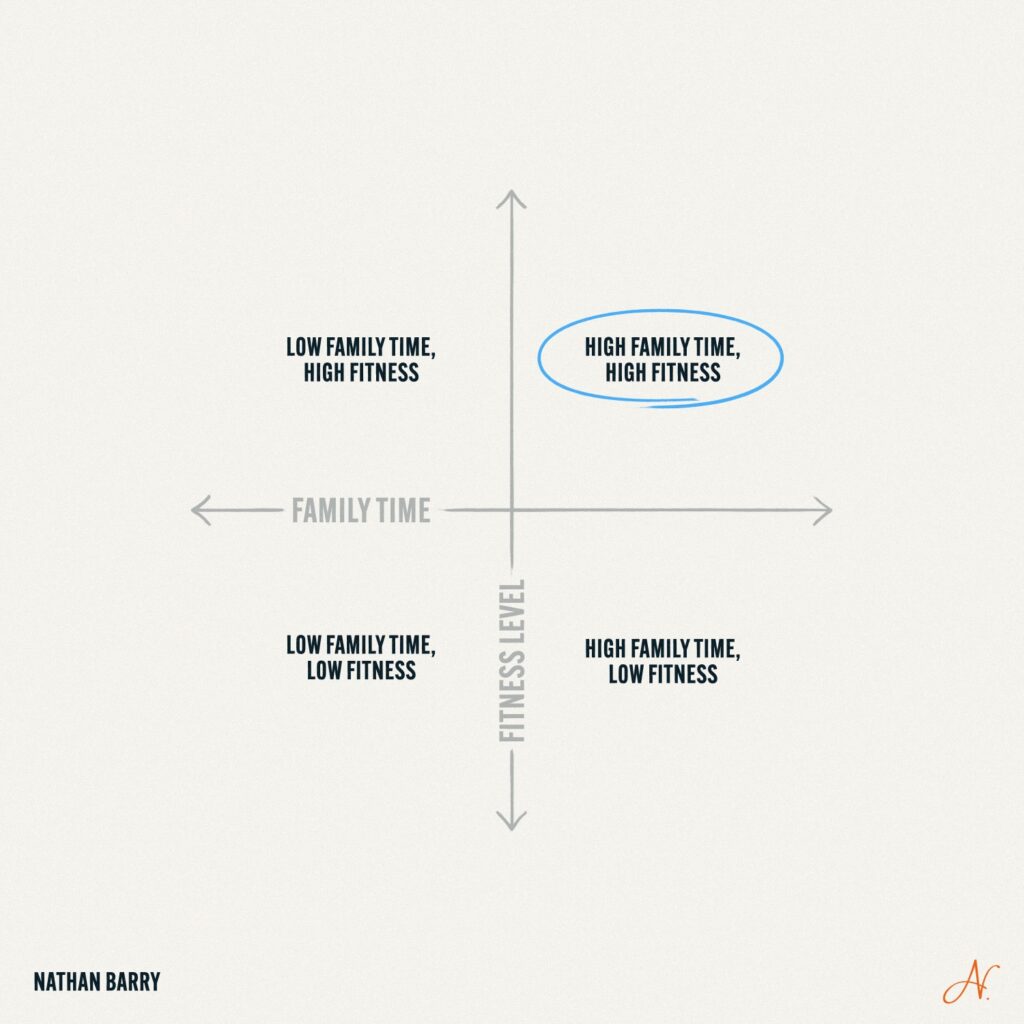

The solution is to take those two things and make them each their own axis.

Double-Axis Reality

Instead of family time versus fitness, you have family time as the X-axis and fitness as the Y-axis. This creates four quadrants where you can plot different approaches:

- Low family time, low fitness (bottom left)

- High family time, low fitness (bottom right)

- Low family time, high fitness (top left)

- High family time, high fitness (top right)

When you map this out, you start finding examples that break your original frame. Busy executives who work out with their families. Parents who bike to work and coach their kids’ sports teams. People who’ve made fitness a shared family value rather than a competing priority.

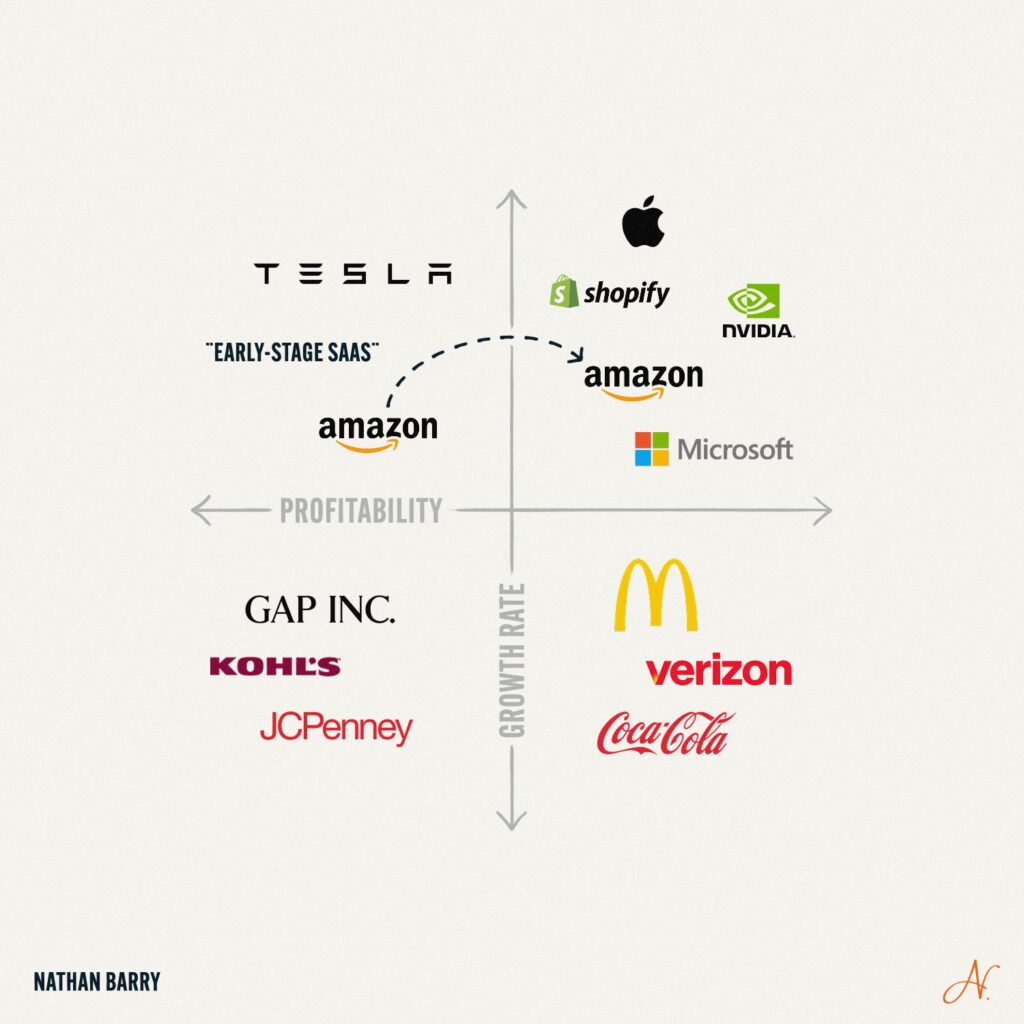

Why this matters for your business

Take the classic business trade-off: growth versus profitability. Entrepreneurs often assume rapid growth requires sacrificing profits, or that focusing on profit margins slows growth.

But look at the exceptions. Amazon moved from high-growth with zero profit margins to high-growth while being quite profitable. Shopify maintained strong growth over recent years while significantly improving profitability and even reducing headcount.

These companies didn’t accept the single-axis assumption. They asked: “What would have to be true to achieve both high growth and high profitability?” Then they worked backward from that question.

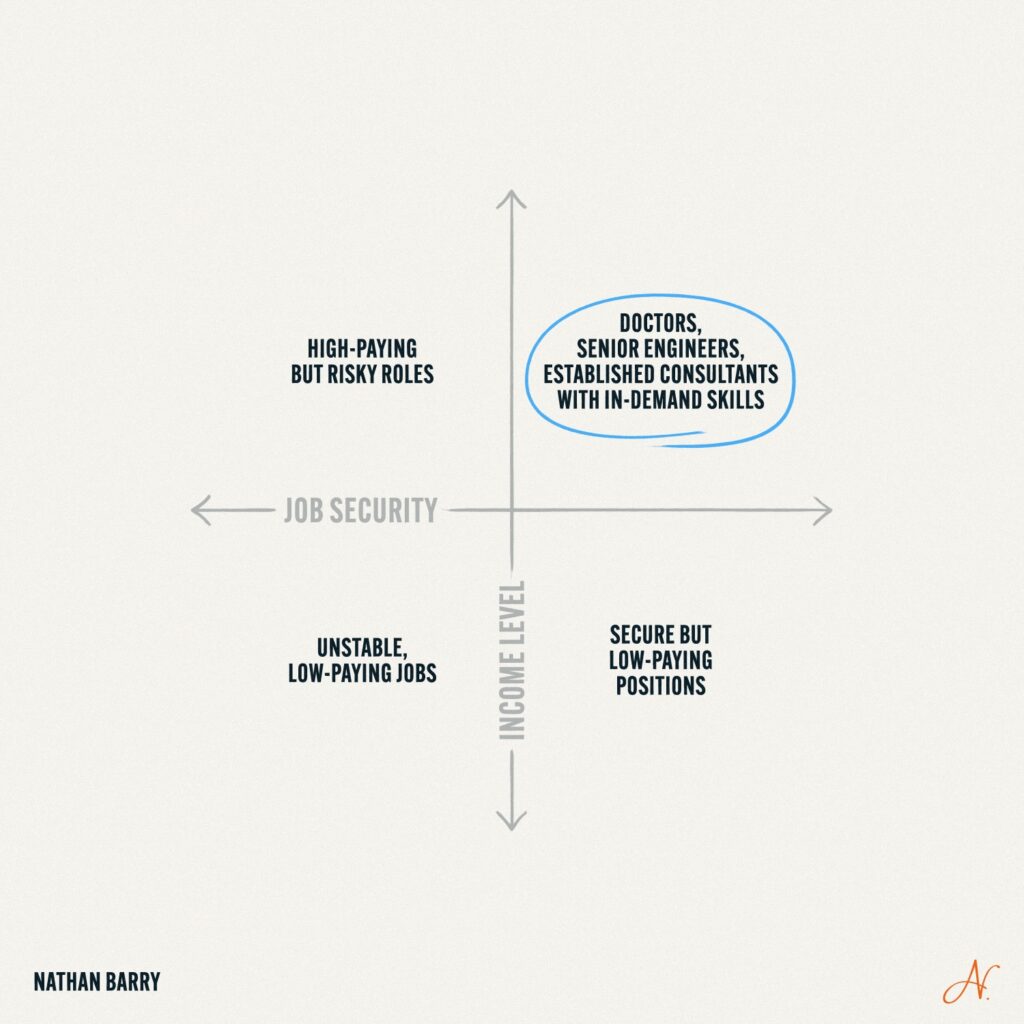

Where else this shows up

Once you know how to spot it, you’ll see the Single-Axis Fallacy everywhere:

Job security versus high income. Many assume stable jobs pay less than risky ones. But the highest earners often have the most job security because they’ve built valuable, in-demand skills.

Quality versus quantity of output. Creators think they have to choose between publishing frequently or maintaining high standards. But successful creators develop systems that let them produce both consistently good work and lots of it.

Saving money versus enjoying life now. Personal finance advice often frames this as either/or. But people who build wealth while living well focus on optimizing their spending rather than minimizing it.

How to escape single-axis thinking

Here are three steps when you spot a single-axis fallacy:

- Create the grid – Put each concept on its own axis instead of opposite ends of one line

- Find the outliers – Identify 3-5 real examples that achieve both outcomes successfully

- Ask “What would have to be true?” – List the conditions that would make both things possible simultaneously

The framing matters. When you go from a single axis to two axes, it opens up possibilities. You can still prioritize one over the other when needed, but you’re no longer trapped by the assumption that having more of one means less of the other.

What single-axis fallacies have you come across?

What double-axis realities are you missing?

Leave a Reply